Literate Programming with Org-mode

I’ve described at length how I use Emacs and Org as a project management tool. As part of my process, I frequently use Org as a lab notebook, in which I keep track of various bits of data and record both the code I run and various parameters I used in the process. My workflow requires (1) running code, (2) logging the results, and (3) including my own thoughts and analysis in between, a programming paradigm known more generally as literate programming.

A number of folks on Reddit and irreal.com have pointed out that I don’t dive deep enough to really call the content in this post literate programming. Perhaps a more appropriate title would include Literate Scripting; regardless, the content I present here is still an integral part of my Emacs-based workflow.

A number of folks on Reddit and irreal.com have pointed out that I don’t dive deep enough to really call the content in this post literate programming. Perhaps a more appropriate title would include Literate Scripting; regardless, the content I present here is still an integral part of my Emacs-based workflow.

Org makes it easy to asynchronously execute code for multiple programming languages (and even allows for remote code execution over ssh). For instance, on a recent project of mine I had a few shell scripts that I would occasionally run that would loop through some data files I was generating on a remote machine and return some statistics about them; Org makes it possible for me to do this without having to leave my notes. In this article, I’ll go over a few use-cases that illustrate the utility of using Emacs with Org for coding projects and walk you through some of the functionality I couldn’t live without.

Org-Babel Basics & Remote code execution

Org makes it easy to include source code blocks alongside text passages and then execute it with Org Babel. Setting up Babel is pretty simple:

lisplisp;; Run/highlight code using babel in org-mode

(org-babel-do-load-languages

'org-babel-load-languages

'(

(python . t)

(ipython . t)

(sh . t)

(shell . t)

;; Include other languages here...

))

;; Syntax highlight in #+BEGIN_SRC blocks

(setq org-src-fontify-natively t)

;; Don't prompt before running code in org

(setq org-confirm-babel-evaluate nil)

;; Fix an incompatibility between the ob-async and ob-ipython packages

(setq ob-async-no-async-languages-alist '("ipython"))The anatomy of a source code block is reasonably simple: each begins with #+BEGIN_SRC, followed immediately by the name of the language, then the code you wish to include, and finally closes with #+END_SRC. Here’s a simple example in Python:

#+BEGIN_SRC python :results output

import random

random.seed(1)

print("Hello World! Here's a random number: %f" % random.random())

#+END_SRC

#+RESULTS:

: Hello World! Here's a random number: 0.134364Running C-c C-c while the cursor is inside the source block will execute the Python code block in place and produce the result you see above. If you pasted this src block into an Org file, you should notice that it is automatically syntax highlighted as well. Executing C-c ' inside the block will open a separate buffer in which you can edit the block.

Setting :results output captures the printed output of executing the code block; an exhaustive list of arguments for src blocks can be found in this Org Babel reference card.

Setting :results output captures the printed output of executing the code block; an exhaustive list of arguments for src blocks can be found in this Org Babel reference card.

Setting the arguments of a src block is a powerful tool. For instance, changing the :dir argument changes the base directory in which the code is run. This is useful for running simple bash scripts:

#+BEGIN_SRC bash :dir ~/Desktop

pwd

#+END_SRC

#+RESULTS:

: /Users/Greg/DesktopWhere this functionality really shines is in the ability to execute code on remote servers. The :dir argument can be set to paths using scp syntax, and Emacs will take care of the ssh into the remote machine, running the code, recording the output, and inserting it into the buffer.

#+BEGIN_SRC bash :dir /user@127.0.0.1:

pwd

echo $USER

hostname -I

#+END_SRC

#+RESULTS:

: /home/user

: user

: 127.0.0.1Of course, you should replace user@127.0.0.1 with a username and IP address of your choosing. Note: I would highly recommend that you use the remote code execution functionality only for machine in which you have an ssh key installed. Emacs will prompt you with a password whenever the keys are not installed, but I’ve had it hang on occasion, which can be frustrating when I’m in the middle of a task.

Code execution in Emacs is synchronous by default, meaning that you will be locked out of editing while the code is being run. Fortunately, the fantastic ob-async package allows for asynchronous code execution with the :async arg, meaning that you can still use Emacs while the code snippet is run in the background. Once the package is installed, simply include :async t to the source code block and run it again:

There are some small things you give up by using the ob-async package. In particular, the :session functionality is absent in general, which otherwise allows variables and function definitions to persist across blocks of code.

There are some small things you give up by using the ob-async package. In particular, the :session functionality is absent in general, which otherwise allows variables and function definitions to persist across blocks of code.

#+BEGIN_SRC bash :dir /user@127.0.0.1: :async t

pwd

echo $USER

hostname -I

#+END_SRC

#+RESULTS:

: 0ddf0124c8fcb26d53fdba83dc4773f6While the code block is running, the RESULTS drawer is populated with a random hash. When the block is finished executing, the hash will be replaced with the actual result.

Example: Setting up a Python virtual environment

Most examples that use Org Babel seem to focus on a particular language, yet many of the projects I set up actually involve the interplay between multiple languages. Here, we’ll set up a Python virtual environment (in bash), set up an iPython workbook, and then use the resulting environment to generate a plot, which we can view inline. Package management in Python can be a pain, which is why using a virtual environment is important for making reusable development environments. If you want to follow along, be sure to install ob-async, pyvenv, and ob-ipython within Emacs. As one might expect, I wrote this entire section using my literate programming setup. Since my blog’s syntax highlighting didn’t play nice with the Org syntax, I’ve broken the code blocks into manageable chunks.

Rather than set the properties of each BEGIN_SRC block individually, I often find it useful to set certain properties at the level of each Org header, which I do in the :PROPERTIES: drawer:

* Creating a Python virtual environment

:PROPERTIES:

:header-args: :eval never-export

:header-args:bash: :exports code

:header-args:elisp: :exports code

:header-args:ipython: :exports both

:END:Notice that, in addition to setting :header-args: I have also set a number of language-specific arguments as well. For instance, I have set :header-args:elisp: :exports code, which means that for any Emacs lisp code blocks, whenever I want to export this Org file to a different format (like a PDF) for sharing, only the code will be included in the export and the RESULTS drawer will be ignored.

My first step is to set up the Python virtual environment. For convenience, I will put it on my Desktop, which I can do by setting :dir ~/Desktop in the src block properties, and name it py2_venv:

#+BEGIN_SRC bash :dir ~/Desktop :results drawer

pwd

virtualenv py2_venv

#+END_SRC

#+RESULTS:

:RESULTS:

/Users/Greg/Desktop

New python executable in /Users/Greg/Desktop/py2_venv/bin/python

Installing setuptools, pip, wheel...done.

:END:The results suggest that everything finished as expected and that the virtual environment is now on my Desktop. With that complete, we need to activate the virtual environment within Emacs. This is done with the pyvenv-activate command provided by the pyvenv package as follows:

For whatever reason, I found that installing packages in the virtual environment was only practical after activating the virtual environment inside Emacs, since this seems to modify the python path.

For whatever reason, I found that installing packages in the virtual environment was only practical after activating the virtual environment inside Emacs, since this seems to modify the python path.

#+BEGIN_SRC elisp :results silent

(pyvenv-activate "~/Desktop/py2_venv")

#+END_SRCWith the virtual environment activated, installing a few packages via pip is pretty simple.

The additional ipython and jupyter packages are for using iPython (instead of Python) with Babel. There are a couple niceties provided by the ob-ipython package that you don’t get from the base Python install, so I’d recommend looking at the documentation if you’re interested in Python development.

The additional ipython and jupyter packages are for using iPython (instead of Python) with Babel. There are a couple niceties provided by the ob-ipython package that you don’t get from the base Python install, so I’d recommend looking at the documentation if you’re interested in Python development.

#+BEGIN_SRC bash :results drawer :async t

pip install ipython jupyter_client jupyter_console numpy matplotlib

#+END_SRCSince installing packages via pip can sometimes take a while, waiting for the code to finish can be a massive inconvenience, and I’ve included :async t in the arg list so that the installations will run in the background. Once this is done and the virtual environment is set up, running Python code within iPython is as straightforward as one might expect:

#+BEGIN_SRC ipython :results drawer :async t :session py2session

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

#+END_SRCNotice that, in addition to running the code asynchronously, I have also provided :session py2session to the iPython src block. Sessions are extremely useful, since they allow you to set variables, define functions, import packages, etc. within one src block and have them persist to other src blocks with the same session name. Now, having imported the requisite packages, we can generate a plot:

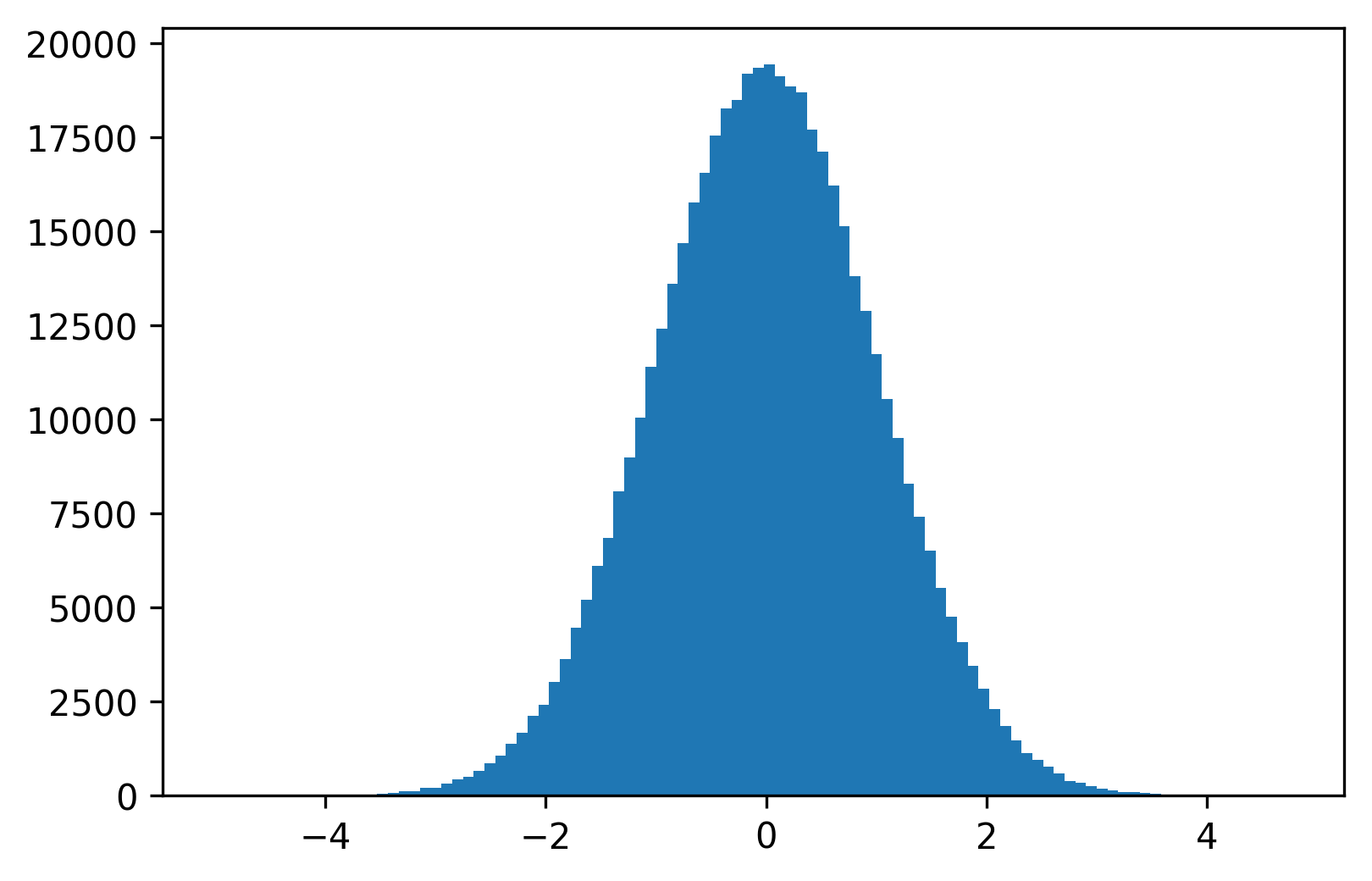

#+BEGIN_SRC ipython :results drawer :async t :session py2session

fig=plt.figure(facecolor='white')

plt.hist(np.random.randn(500000), bins=100);

#+END_SRCHaving set %matplotlib inline in the previous block, the resulting plot is saved to a temporary directory and appears inline. Expectedly, the histogram shows a Gaussian distribution:

Additional Resources

There are plenty of other resources on using Emacs and Org Babel for literate programming. In addition to the guide to Org Babel there’s also the fantastic Literate DevOps guide and accompanying video summary by Howard Abrams. If you enjoyed this post and are left wanting more, I’d recommend checking out Howard’s guides: both are fantastic. Also useful is the Org-mode guide to working with source code.

Feel free to let me know how this short guide may be improved in the comments below or on Reddit.