The Physics of Maxwell's Equations

The original motivation for this post was the first homework prompt I encountered in graduate school at MIT, while I was taking a course on linear optics:

The course was taught by Prof. Jim Fujimoto, who pioneered optical coherence tomography.

The course was taught by Prof. Jim Fujimoto, who pioneered optical coherence tomography.

Describe the Physics behind Maxwell's Equations.

Deceptively simple, the prompt was designed to encourage me and my peers to think more about the physical implications of the well-known Maxwell’s Equations, which detail the behavior of electromagnetism, one of the fundamental forces of nature. Our responses were not supposed to be steeped in derivations or overly sophisticated equations, but were instead supposed to build intuition. I was quite proud of my response (and it earned the highest grade in the class), so I have included it here in an effort to convey my passion for these elegant, and profound, equations.

Here, I aim to delve into the fundamentals of electromagnetism, with the goal of making this post accessable to those who may not have a particularly strong mathematical background while including enough analysis so that it may be useful and interesting to those who do. More than anything, the purpose is to imbue the reader with some of the physical intuition behind electromagnetism.

Introduction

Electricity and Magnetism are among the most fundamental forces of nature. The electric and magnetic fields, which are measures of the strength of electric and magnetic forces, permeate the space all around us. Mathematically, we represent them as vector fields, basically arrows (each with their own magnitude and direction) at each point in space. Electric charge $Q_e$ and magnetic charge $Q_m$ will feel forces from the various fields, thereby allowing us to measure them. Ultimately, the electric and magnetic fields represent the way in which charged particles interact with one another, just as celestial bodies gravitationally attract.

As we shall see throughout the remainder of this post, charged objects are both affected by the presence of these fields and capable of creating new ones, thereby tethering the seemingly intangible fields to physical objects which fall into our standard, observational reality. Understanding electricity and magnetism allows us to understand behavior at all physical scales, helping to explain physical phenomena ranging from why protons and electrons are attracted to one another in atomic nuclei to how light can be generated by the motion of charged particles.

Maxwell’s Equations

An electrically charged particle will feel a force $\mathbf{F}$ accordingto the well known Lorentz Force equation:

\[\mathbf{F} = Q_e \left[ \mathbf{E} + \mathbf{v} \times \mathbf{B} \right]\]where $\mathbf{E}$ is the electric field, $\mathbf{v}$ is the motion vector of the charged particle (yes, the particle must be in motion to feel a magnetic field), and $\mathbf{B}$ is the magnetic field. How these fields are generated, though, will be the subject of discussion in the rest of this post.

Underpinning the entirety of the field of Electricity & Magnetism, or E&M, are four equations known collectively as Maxwell’s Equations:

\[\begin{align} \nabla\cdot \mathbf{E} &= 4 \pi \rho_e \label{meq_intro_a}\tag{1a}\\\\ \nabla\cdot \mathbf{B} &= 4 \pi \rho_m \tag{1b}\\\\ -\nabla\times\mathbf{E} &= \frac{1}{c} \frac{\partial\mathbf{B}}{\partial t} + \frac{4 \pi}{c} \mathbf{J}_m \tag{1c}\\\\ \nabla\times\mathbf{B} &= \frac{1}{c} \frac{\partial\mathbf{E}}{\partial t} + \frac{4 \pi}{c} \mathbf{J}_e\tag{1d} \end{align}\]The learned reader will recognize that this is not the form of Maxwell’s Equations traditionally listed in textbooks. In particular, a few oft-ignored terms [$\rho_m$ and $\mathbf{J}_m$] have been included to highlight the symmetry inherent to the equations, something which will be discussed later on.

The Divergence

In order to begin to understand these equations, I ask that you first envision a light bulb, or, rather, a perfectly spherical light source, one which radiates light uniformly in all directions. As you get closer to or farther from the light, it appears to get brighter and dimmer, until, once one is sufficiently far away, the light can no longer be observed by the naked eye. You should already understand that changing your distance from the light source will change how much total light enters your eye, rather than actually modifying the strength of the source. What your eye is measuring is known as luminous flux, where “flux” is the strength of the light at the location of your eye multiplied by the area your eye takes up. It should come as no surprise to hear that the total luminous flux leaving the source is a constant, as the light is not actually dimming and brightening as you change your position. However, your distance from the bulb changes the amount of flux you measure, so that the light will appear to change in strength. Mathematically, this physical principle is written as follows:

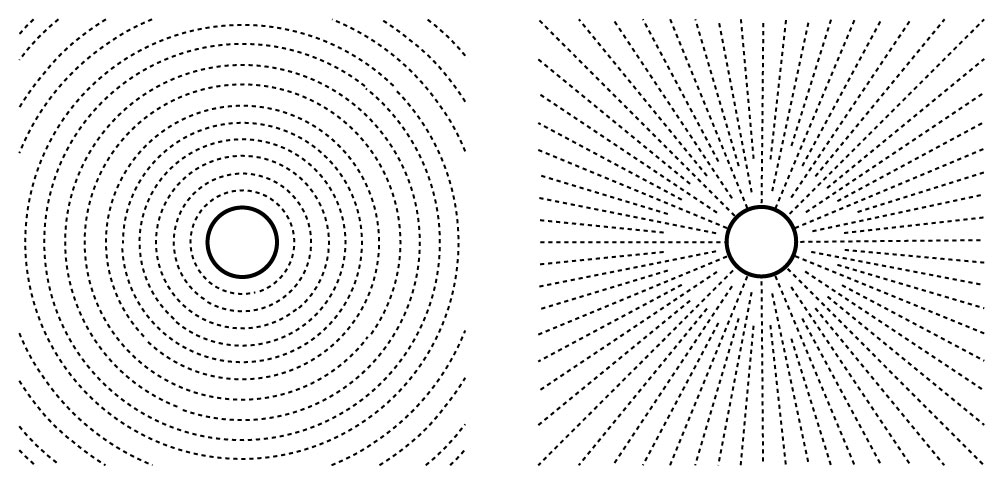

\[\text{Bulb Strength} \propto \text{Total Flux} = \sum \text{Individual Fluxes} = \int\limits_S d\mathbf{a}\cdot\text{Light Intensity}\]where the final term represents the integral [a differential sum] over all the light intensities at each differential area $da$ on an arbitrary closed surface $S$ which surrounds the light. To avoid being bogged down in the mathematical notation, always keep an image in the back of your mind, of a light source completely surrounded with photodetectors. So long as the light is completely enclosed within the photodetectors, the total amount of flux they measure will be a constant, regardless of their configuration. This is shown in the sketch in the figure below.

The uninitiated reader may wonder why I devoted a considerable portion of this essay thus far to an almost trivial discussion of a light bulb, however, this picture is key to understanding the first two of Maxwell’s Equations. Many phenomena in nature behave like this simple system and, as it turns out, the seemingly mysterious electric and magnetic fields, $\mathbf{E}$ and $\mathbf{B}$, are generated by their respective charges just as light is generated by a light source. As such, for the electric field, we can posit that:

\[\text{Total Electric Charge $[Q_e]$} \propto \text{Total Electric Flux} = \int\limits_S d\mathbf{a}\cdot\text{Electric Field Intensity} = \int\limits_S d\mathbf{a}\cdot \mathbf{E}\]This is just like the light bulb! This is one form of the first of Maxwell’s Equations, which effectively states that static electric charges will “radiate” electric fields $\mathbf{E}$ in an outward direction, like light from a light source: i.e. electric/magnetic charge is a source of electric/magnetic fields (respectively).

However, one may notice that this equation looks nothing like Equation \eqref{meq_intro_a}, the first of Maxwell’s Equations above. This is because Maxwell’s Equations are much more useful, in many ways, when they are written in what is known as their differential form. Rather than carrying around the information of a particular volume or surface which is required of the integral form of Maxwell’s equations the differential equations have no such dependencies, since they represent the same ideas presented in the integral form, yet over an infinitesimally small volume. The differential equation form of the first Maxwell’s Equation is given by

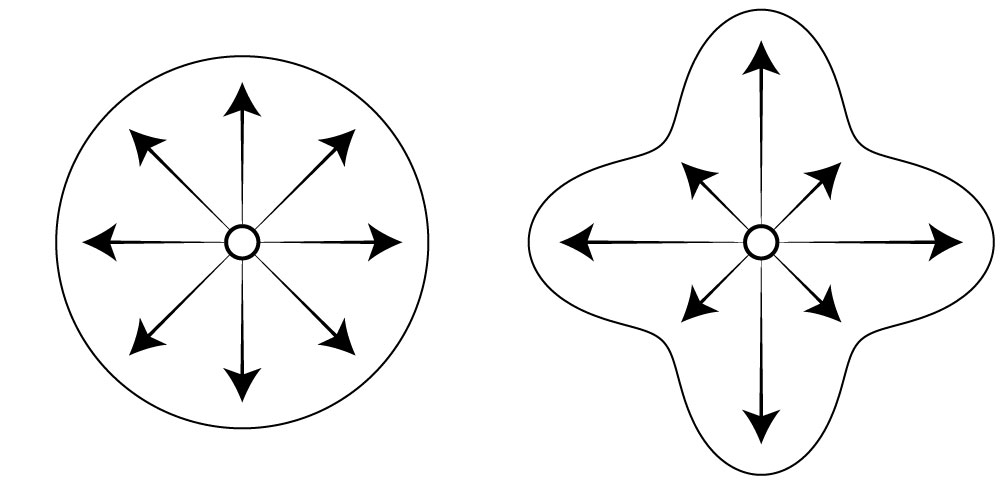

\[\nabla\cdot\mathbf{E} = 4 \pi \rho_e\]The $4 \pi$ comes about as a geometric factor necessary to relate the two (think about Surface Area of a sphere being equal to $4 \pi \cdot r^2$). In order to understand the above equation, one may simply superimpose our previous picture of the light source onto this new equation: given some charge per unit volume $\rho_e$ (which is a tiny element of charge within th total charge $Q_e$), the electric field at a particular point will have a finite divergence, notated as “$\nabla\cdot$”. The divergence is a vector derivative operation (akin to the derivative in a single variable calculus) which describes the rate at which a vector field is “sourced”, just like the light from the bulb. For some visual stimuli, I have included some sketches of vector fields below:

In accordance with these definitions, we can see that if there is some stationary electric charge distribution in a region, each element of that distribution will contribute to sourcing outward (or inward) pointing electric fields, emanating from its location. Similarly, you may notice that the second Maxwell’s Equation has the exact same form, such that the divergence of the magnetic field (the strength of the radially oriented sourcing of $\mathbf{B}$) is equivalent to the static magnetic charge distribution $\rho_m$ at a particular point.

The Curl

Up until this point, I have taken great care to emphasize that the first two of Maxwell’s Equations describe the generation of $\mathbf{E}$ and $\mathbf{B}$ from charge distributions which are stationary, and have avoided discussing what occurs when the charges begin to move. It is a truly remarkable discovery, one of the great revelations in the history of physics, that electricity and magnetism are intrinsically linked to one another. Moving charges of one type, magnetic or electric, will create fields of the opposing type! The most familiar example of moving charges are the electrons which move about in a metal wire hooked up to a battery. As it would turn out, if one holds a very sensitive compass near the wire as it is connected to the battery, it will deflect, indicating the presence of a magnetic field once the electrons in the metal are moving. The question then becomes, in what direction are the magnetic field lines created, and how does their strength vary as one travels farther from the wire.

In order to understand the generation of magnetic field lines from moving electrons in a wire, I will describe a similar case: that of a rotating paddlewheel in a pool of water. Imagine a small paddlewheel attached to a drill, so that rotating it quickly is not an issue. The paddlewheel is dipped in the center of a large bucket of water and the drill is turned on. After a time the water all throughout the bucket will be rotating at varying rotational speeds. While the angular speed of the water decreases as one gets farther from the rotator, the total circulation remains the same. The circulation is a measure of how much fluid goes around the paddlewheel over a certain period of time, typically as a function of distance from the center, such that:

\[\text{Drill Speed} \propto \text{Circulation} = \int_C d\mathbf{s}\, \cdot \text{Water Velocity} \label{eq:Circulation}\tag{2}\]where the integral is over some closed loop $C$ which encloses the paddlewheel. For the system with the drill, drawing larger circles means that you encounter more slowly moving water, so that the total amount of water moving along the path of the circle remains the same.

As you may have guessed, this is the basic geometry behind the generation of field lines from moving charges; the direction of motion of the electron corresponds to the orientation of the drill while the magnetic field lines form in circular patterns, decreasing in strength as one moves farther from the wire (just like with the paddlewheel). The integral form of this principle matches Equation \eqref{eq:Circulation}:

\[\text{Electric Field Circulation} \propto \int\limits_C d\mathbf{s}\cdot\mathbf{B}\]but we wish, as before, to rewrite this in its differential form, which can be used more generally. To do this, we must introduce a new differential operation called the curl, notated as “$\nabla\times$”. Just as the divergence related the sourcing of outward oriented field lines to a piece of charge, the curl relates the sourcing of circulating field lines to a piece of current. In integral form, the ideas presented here can be written as:

\[\nabla\times\mathbf{B} = \frac{4 \pi}{c}\mathbf{J}_e \label{eq:BJ}\tag{3}\]where, the factor of $4 \pi$ is again a geometric one. Additionally, a factor of one over the speed of light $c$ has been introduced. This is because the generation of the magnetic field from electric charges is a relatively weak process unless the current is very strong. Even though the fields are coupled, nature wants to be sure that we won’t generate massive magnetic fields unless the charges in motion approach the speed of light. To more easily understand the above equation, you should superimpose our picture of the drill onto both sides of the equation. Simply imagine that the electric current density $\mathbf{J}_e$, the electric current per unit volume, is a microscopic version of our paddlewheel, which creates a differential circulation in the magnetic field $\mathbf{B}$ which surrounds it. As larger current distributions are created, each differential element of $\mathbf{J}_e$ will contribute to the creation of the magnetic field, just like having many tiny paddlewheels or, in the case of the divergence, many small light sources.

A Connection Between the Fields

I mentioned earlier, upon introducing Maxwell’s Equations, that the electric and magnetic fields are intrinsically linked to one another. Sure having electric charge create both electric and magnetic fields, with the strength of the latter depending on how quickly its moving, is fascinating, but one would hardly call that a pure link between the two.

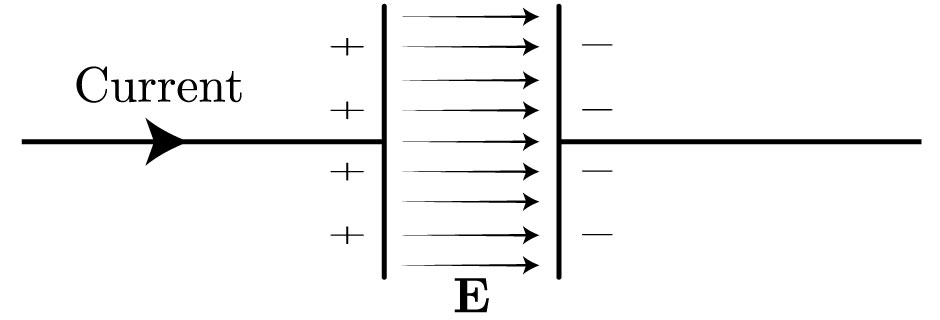

Let’s look back at our wire (no paddlewheel this time around), but rather than a complete wire, let’s say that there is a capacitor at one location, shown in the sketch in the figure below. A capacitor is a device which stores electric charge, typically comprised of two metal plates which face one another. A wire can be cut and a capacitor placed in series with the two broken edges so that positive charge accumulates on one side and negative charge on the other. Based upon once we know from the first Maxwell’s Equation, $\nabla\cdot\mathbf{E} = \rho_e$, we know that an accumulation of charges means that we are sourcing $\mathbf{E}$ fields from the plate with the positive charge and sinking $\mathbf{E}$ into the other. This means that, as the charge on either side increases, so to does the electric field in the gap between the plates.

While it’s fantastic that we have the ability to properly predict what will happen to the electric field in the case of a capacitor hooked up to a battery with a couple of wires, what is happening to the magnetic field $\mathbf{B}$ at this point? We have already discussed that around the wire we are creating magnetic field line circulation, on account of the fact that the curl in the magnetic field is equal to the current flowing through the wire. What happens when reach the point in this simple circuit where there is no more wire and we are left instead with only the capacitor? Does the magnetic field simply vanish? Such a thing would not make much physical sense as we are still having an accumulation of charge (and, therefore, electric fields) within the capacitor. Our expectation that the magnetic fields will still be created is confirmed by experiment, and, even when the wire is broken and a capacitor is inserted, magnetic field curl is still non-zero. This means that Eq. \eqref{eq:BJ} (above) is missing a term. As you may have already guessed from our discussion, this term must be the rate of change of the electric field over time, which is the only physical quantity changing in the gap between the two plates of the capacitor. As such, we find that the complete form of Eq. \eqref{eq:BJ} is:

\[\nabla\times\mathbf{B} = \frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial\mathbf{E}}{\partial t} + \frac{4 \pi}{c} J_e\]which states that the curl of the magnetic field (which, as discussed, corresponds to microscopic sources of circulation in $\mathbf{B}$) is created by both moving electric charges and changing electric fields.

Maxwell’s Equations are also beautifully symmetric, such that the equations describing the generation of the electric and magnetic fields are quite similar to one another. In addition to electric charge creating divergence in the electric field, so too will magnetic field from magnetic charge:

\[\nabla\cdot\mathbf{E} = 4 \pi \rho_e \Leftrightarrow \nabla\cdot\mathbf{B} = 4 \pi \rho_B\]Similarly, the curl of $\mathbf{E}$ is generated by a time varying magnetic field and by magnetic current: \(\nabla\times\mathbf{B} = \frac{1}{c} \frac{\partial\mathbf{E}}{\partial t} +\frac{4 \pi}{c} J_e \Leftrightarrow -\nabla\times\mathbf{E} = \frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial \mathbf{B}}{\partial t} + \frac{4 \pi}{c}J_m\)

One consequence of this is that a permanent bar magnet dropped through a closed circle of wire will create an electric parallel to the wire, thereby creating a current (which, in turn, creates an additional magnetic field because of $\nabla\times\mathbf{B} = J_e$, etc.).

You will notice, however, that the equations are not completely symmetric, as there is a minus sign introduced in front of $\nabla\times\mathbf{E}$ in the previous equation. This serves a very important purpose: making sure that the fields do not grow infinitely. When I told you both that time varying electric fields can create magnetic fields and time varying magnetic fields can create electric fields, you may have been a little bit skeptical: “Does this process not create electric and magnetic fields onto infinity?”. The minus sign serves to limit this creation process and, rather than grow forever, the field generation limits itself. Such behavior is actually what leads to the generation of light, which is a traveling wave (similar to those in water) of rapidly oscillating electric and magnetic fields. If the minus sign were not there, the same sorts of processes which we know of as light, a.k.a electromagnetic waves, would become interminably growing electric and magnetic fields, and the universe as we know it would not exist.

Magnetic Charge

This concludes the foundation of Maxwell’s Equations, however, there are a number of “complications” which change their form. First, and perhaps the most shocking, is that, while we’ve all heard of electrons and protons, which are units of electric charge, none of us have ever heard of something which carries magnetic charge. This is because no magnetic charges have ever been observed and, for reasons far beyond the scope of this derivation, none may exist at all. As such, $\rho_m$ is identically equal to zero and, because there are no charges to move in the form of a current, so too is $J_m$. Therefore, Maxwell’s Equations typically have the following form:

\[\begin{align} \nabla \cdot \mathbf{E} &= 4 \pi \rho_e \\\\ \nabla\cdot \mathbf{B} &= 0 \\\\ \nabla\times\mathbf{E} &= -\frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial\mathbf{B}}{\partial t} \\\\ \nabla\times\mathbf{B} &= \frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial\mathbf{E}}{\partial t} + \frac{4 \pi}{c}\mathbf{J}_e \end{align}\]Keep in mind that, while the symmetry is no longer immediately apparent, this is merely a simplification which eliminates some of the terms, rather than introducing new ones. The condition that no magnetic charge exists is often more technically stated that there are no magnetic monopoles, which is a restatement of the fact that the divergence of the magnetic field is always exactly equal to zero.

Relativity

Electric and magnetic fields can be seen to relate to one another in an even deeper level, by applying some of the more basic principles of relativity. Though relativity (especially in the general form introduced by Einstein) seems like a rather daunting concept, I assure you that this will be no more difficult to understand than anything discussed above. Let’s say, if only for the purpose of whimsy, you are driving around in your car with an electron in the passenger seat. Previously, I established that moving charge, even an electron, will create a magnetic field (along with the electric field it always sources). Now, for passersby, the electron is moving at the speed of the car, and they will be able to see a magnetic field, however, since you and the electron are going at the same speed in the vehicle, you will not see a magnetic field at all. You may ask, “what’s going on here?” but, in reality, this effect stems from the idea that the electric and magnetic fields are simply different manifestations of the same fundamental force.

Recognizing that the electron is moving in one reference frame and not moving in another is not a difficult concept, since we observe this simple phenomena when we drive to work in the morning. However, the transformation of fields is a necessary consequence of how they are defined. This same process can be generalized, within the framework of Einstein’s special relativity, into a mechanism which allows us to convert magnetic fields into electric fields, much like in this case, and vice versa for particles which are moving at unbelievably high speeds.

Conclusion and References

This illustration of Maxwell’s Equations is but a small picture of how I perceive the universe around us. I have touched upon a physical picture of all the phenomena directly described by these four elegant equations, without (hopefully) getting too bogged down in the rigorous derivations of each.

The only reference I used for this essay was Jackson’s Classical Electrodynamics, from which I used only the form of Maxwell’s Equations in the presence of magnetic monopoles.